Today’s song is Trying by Bully, which has a sort of a fin de siècle riot-grrl aesthetic. You can almost feel the band tapping through their iPhones looking for the right filter to mimic a badly calibrated Super 8 camera, trying to figure out which vibes of the past to throw into the pastiche, which ones to discard.

Also about trying and also with 1990s vibes, a Slate piece that epitomizes the genre I have come to think of as “Gen-X career disillusionment personal essay.” Obviously this is a generalization so broad as to be nearly meaningless, but these pieces all do seem to follow a pattern, and represent a specific strain of thought and style from people who are roughly my age. The authors are mostly (but not entirely) white men, and they’ve all obviously read Denis Johnson and Douglas Coupland at a formative age. The pieces generally run to a few thousand words: too long for print, too long for 21st century attention spans, perfect for what the authors probably feel was the best era of internet writing.

A typical example is heavy on cynical participation in corporate life. It’s almost always got some vague reference to bad behavior and low places that somehow still manages to provide too much embarrassing information. In this case we find it in the first paragraph: “…in the Johnson County, Iowa, jail, where I spent July 4 and 5 some years ago for reasons I’d rather not go into…”

In the past five or ten years, the Gen-X personal essay has also added a mandatory acknowledgement that its cynicism is passé. It pauses to note that nobody says “sellout” anymore, to remind contemporary readers that the author’s quaint career-related ambivalence and inner turmoil are coming from the era of the payphone and the rented VHS tape.

Critically, such an essay builds up to a conclusion that is well-styled, evocative, and, if you think about it, somewhere between obvious and pointless. Oh, the author has definitely done a great deal of introspection, and I’m sure there’s some personal growth in the writing of this essay, or in the therapy that made the introspection possible, but at the end of it, has the reader gained any insights? Is the reader any richer after what is, in essence, a short description of the sales and persuasion business in three of its least prestigious forms: jailhouse raconteur, telemarketer, and panhandler?

Gosh, are you telling me that sales is a dirty business? That people doing white collar jobs aren’t actually any better than people doing blue-collar work? That seamy and depressing soul-sucking labor and dead-end jobs can happen at any point on the economic spectrum? A truly novel insight. Arthur Miller couldn’t have done better with a smile and a shoeshine and a dead dream.

The narrator of all of these essays is almost always an example of elite overproduction, or at least someone with a degree working a job that they feel is beneath their dignity. It helps if they’re self-aware enough to realize that they’re being both pretentious and classist to look down upon their job rather than just find it irritating. Was the first of these groundbreaking, or was it already a cliche when it was printed?

And yet, as much as I mock them, these sorts of essays hit me right in the gut, because how do you persuade yourself to care enough about something to do it well, without caring so much that you tear yourself apart when things go wrong, or when you have to admit that it’s not, in the grand scheme of things, very important?

To really fall right into it: sometimes this genre feels especially relevant to my work life right now, and it makes me feel uncomfortable. Yes, we all know that being an adult in the working world is occasionally alienating. It’s a job. I get up every day and do it. It’s fine. I don’t want to discount the fact that it’s actually a good job, and many parts of it are also important, and helpful, and worthy. I’m proud to have written a flyer about addiction treatment that can be read and understood by someone who is too ashamed to even pick it up. I’m proud to have been able to explain antiretroviral HIV medications in a way that’s legible to people with only marginal English skills. That’s pretty good work. And I work with kind and thoughtful and collaborative people.

But some of my days could easily be the fodder for any number of these depressing cliches about corporate life. For example, I’ve been working on a project to change a corporate tagline from “funded in part” to “brought to you” in the footers of approximately 2,000 health insurance documents. It’s frustrating, and tedious, and it’s a reminder that I’m just a cog in a giant machine. Especially haunting this month are the constant reminders that the particular machine I’m working for is so widely reviled that a lot of folks were pretty happy to see one of its leaders gunned down in the street. (Following the murder, the headline insurers limit coverage of prosthetic limbs, questioning their necessity is a little too on the nose, you know?)

But as I said, cynicism about one’s career is mostly an outdated and embarrassing cliché at this point. So what if I work for an industry everyone hates? It’s a job. It’s fine.

Nailed It

Did I get that formula right? Let’s play that song back and run the checklist:

- Contains one or two very specific details that don’t quite make up for how vague the rest is.

- Acknowledges that nobody’s really too good for any job; still oozes pretentious disdain for this particular job in question.

- Notes that generalizations are inaccurate; still makes broad generalizations.

- Admits that it’s coming from an outdated worldview; does nothing to actually change said view.

- Throws in something heavy or shocking at the close to distract from the fact that the entire piece can be summarized as “having a job can be a grind sometimes.”

Yep.

News

Good news: BBC roundup of some climate & nature breakthroughs in the past year.

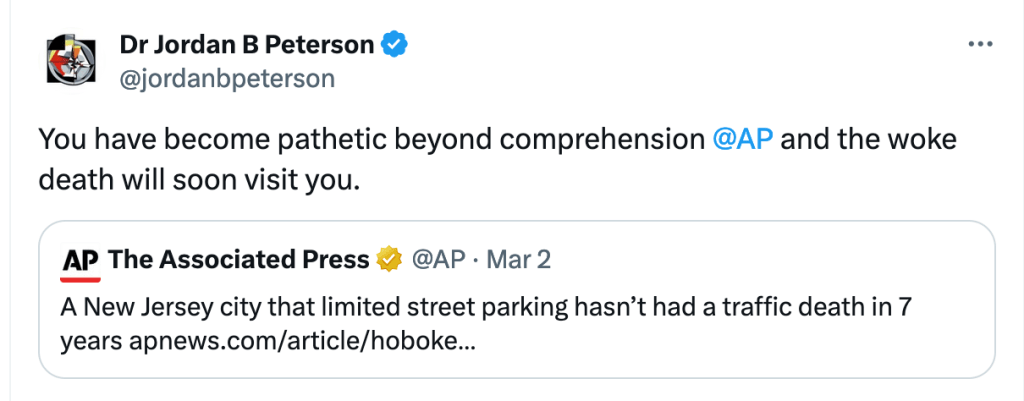

Bad news: Guardian profile of Curtis “Mencius Moldbug” Yarvin, a neoreactionary influencer whose ideas form most of the intellectual framework (such as it is) of contemporary fascism.

Joy

New favorite subreddit: /r/meow_IRL, featuring cats with expressions that match how you feel when you don’t exactly feel your best. It’s got some great ones.